by Robert Romano

“There aren’t enough babies being born in our country… This is a civilizational crisis, and if we’re not willing to spend resources to solve it, we’re not serious about the very real problems that we face.”

That was Sen. J.D. Vance (R-Ohio) in 2021 before he was elected in 2022, speaking at the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s Future of American Political Economy Conference in Alexandria, Virginia, addressing declining fertility rates all around the world that threaten population and economic collapse.

He’s right.

First on the numbers, the amount of newborns is definitely declining, the latest birth rate numbers from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows, to 1.61 live births per woman in 2023.

That’s even lower than it was in 2020 during the Covid pandemic, when it was 1.63 babies per woman, according to CDC data, as the U.S., Japan, South Korea and Europe all continue experiencing significant declines.

The drop in fertility has been a long term trend, from 3.6 babies per woman in 1960 to 1.61 babies per woman now in 2023 after birth control was approved by the FDA in 1960, and combined with women going to college, entering the labor force and deferring child-rearing or foregoing it altogether.

Why is this a problem?

If women have fewer than two babies each, the population has to decline, fewer than one and it collapses, and if they have no babies, within a very short generation the human race will go extinct. It’s that simple.

In the meantime, the collapse of institutions is easy enough to witness, with labor shortages for schools, health care, postal workers and so forth as the Baby Boomer retirement wave continues.

And it’s breaking the budget with comparatively fewer taxpayers, with the explosion of the U.S. national debt, now $34.99 trillion. Since 1963 through 2022, the percent growth of revenues has averaged 6.9 percent a year to its present level of $4.65 trillion, according to data compiled by the White House Office of Management and Budget.

In the meantime, mandatory spending including net interest owed on the national debt has grown an average 8.87 percent a year to its current level of $4.64 trillion.

And discretionary spending has grown an average 5.5 percent a year to its current level of $1.735 trillion.

In fact, since 2011, discretionary spending has only grown 1.99 percent a year.

Meanwhile, since 2011, mandatory spending grew an average 7.7 percent a year.

And revenues grew an average 7.26 percent.

In fact, the entire discretionary budget of $1.736 trillion for 2023 could be eliminated right now — eliminating every department, agency and firing every federal employee including the military — and the budget would still not be balanced as the debt grew by $1.855 trillion in 2023.

In the meantime, Social Security will grow from $1.346 trillion to $2.37 trillion in 2033 amid the Baby Boomer retirement wave, a 76 percent increase.

Medicare will grow from $821 billion to $1.84 trillion, a 124 percent increase.

Medicaid will grow from $608 billion to $928 billion, a 52 percent increase.

These are the drivers of the budget, accounting for 52 percent of all federal spending by 2033. Once interest and other mandatory spending is accounted for, mandatory spending will account 77.8 percent of all federal spending, up from its current level of 72.7 percent.

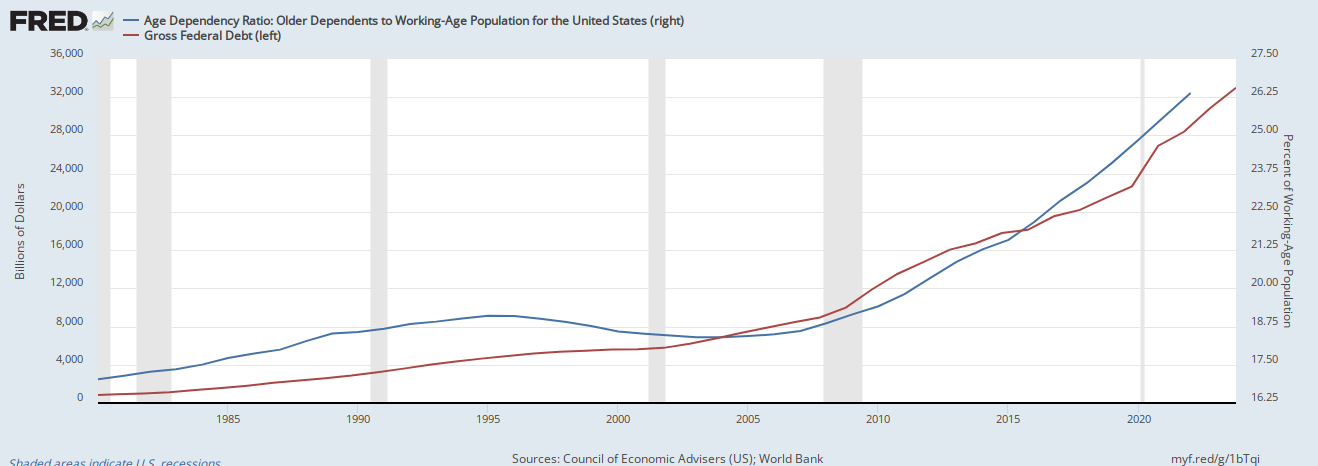

The reason is simple, as the percentage of the working age population over the age of 65 continues to rapidly increase — since 1960, when the FDA approved birth control, it has gone from 16 percent of the population to 26 percent of the population and rising — and with it the $34.5 trillion U.S. national debt, data from the World Bank and the U.S. Treasury shows.

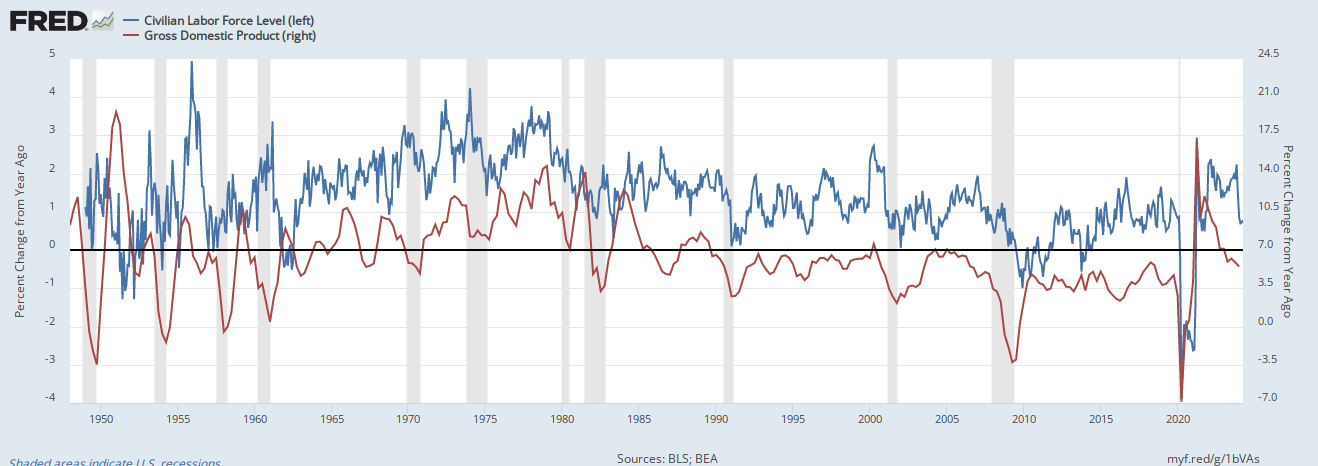

At the same time, as the growth rate of the working age population participating in the civilian labor force has dramatically slowed down thanks to plummeting fertility, so has nominal economic growth, Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis data shows.

There are two simultaneous outcomes that emerge. First, as the population rapidly ages, so too do Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid expenditures that seniors depend on explode.

In the meantime, thanks to slower growth, revenues will continue not to keep pace with expenditures. Revenues will increase from $4.6 trillion in 2023 to $7.4 trillion, a $2.5 trillion or 51 percent increase over ten years. But expenditures will grow even faster, with outlays growing from $6.37 trillion in 2022 to $9.9 trillion by 2033, a $3.7 trillion or a 55.4 percent increase over the next decade.

The White House Office of Management and Budget projects the national debt to skyrocket to more than $50 trillion by 2033, but that’s low-balling it. The debt has grown by about 8 percent a year since 1980 once recessions and wars are factored. At that rate, it should be about $65 trillion to $70 trillion by 2033 and $100 trillion by 2037 or so, well north of 200 percent debt to GDP.

The reason is because there are comparatively fewer taxpayers versus those receiving benefits as the structural deficit widens due to the drop in fertility.

But that’s enough to make your eyes bleed. Imagine it more simply: If a village has 100 people, 50 men and 50 women, and they only have one child per couple, the next generation will only have 50 people, and 25 the generation after that, who will need to take care of 150 older villagers. It’s unsustainable, and is precisely the trajectory we are headed for.

The saying goes, when you less of something, you tax it, and when you want more of something, you subsidize it.

Towards that end, Vance in 2021 supported a proposal by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) that would dramatically expand the child tax credit to $6,000 per child under the age of 13 for single parents, and $12,000 per child under the age of 13 for married couples.

Vance said of Hawley’s proposal at the time, “Lot of ideas out there for how to directly help parents instead of giving them only one option. This is a good one.”

That works out to $78,000 of tax credits for single parents and $156,000 for married parents over the first 13 years of the child’s life, a double incentive not only to have children, but to go further and get married.

And on the Charlie Kirk podcast in 2021, Vance further summarized his thoughts that incentives should be used to encourage family formation, stating, “So, you talk about tax policy, let’s tax the things that are bad and not tax the things that are good… If you are making $100,000, $400,000 a year and you’ve got three kids, you should pay a different, lower tax rate than if you are making the same amount of money and you don’t have any kids. It’s that simple.”

At the Conservative Political Action Conference in March 2023, former President Donald Trump also expressed support for what he is calling “baby bucks,” stating, “We will support baby bonuses for a new baby boom! I want a baby boom! You men are so lucky out there — you are so lucky, men.”

Another approach might be to simply front-load the tax credits into the child’s earlier, pre-school years, for example, $40,000 per baby, with $20,000 upfront and $4,000 a year for each of the following five years. The idea would be to foster a baby boom. Additional consideration could be given to incentivizing marriage, say, an additional $10,000 upfront for married couples having new children.

That could reduce the overall cost, although it would still be costly, $450 billion for every 10 million new babies, assuming equal amounts of single and married households. But that’d still be cheaper than the Hawley proposal, which might come out to $1.17 trillion for every 10 million new babies. It also might be more effective, if by front-loading the credits it results in immediate attempts at child-rearing.

Either approach would ultimately pay for itself, since individuals who work ultimately end up paying in excess of either $50,000 or $117,000 in taxes over their careers. And what we get in return is a growing, more robust generation of Americans.

Currently, about 3.7 million babies a year are born. But with incentives, that can be increased quickly.

It would be inflationary, for certain, as it was in the postwar baby boom. But so are labor shortages that contribute to supply shortages. Overall, a declining population could be deflationary long term, which has its own set of problems as was seen during the Great Depression. And rather than other proposals for universal basic income so that people can work less to pursue hobbies, by focusing on boosting family formation, the goal is to build the next generation of doctors, engineers, plumbers, farmers and so forth. We need not sacrifice our society’s emphasis on education.

To have a sustainable, highly educated country and economy, we need a sustainably growing population that is not dependent on foreign immigration. And as the average age of immigrants continues increasing — the median age of immigrants in 2022 was 47 — at best it is a temporary offset but ultimately contributes to the aging population.

Other alternatives including banning birth control and defunding colleges and universities might be a political lead balloon, not be successfully implemented and destroy the political party that adopted those policies.

It’s all about incentives. And the consequences for not getting the mix of incentives right appears to have dire consequences. In short, if we want to continue to be a growing, prosperous country, it’s time to get busy!

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

Sorry folks, but I am way past the point of being angry for having to pay for other people’s kids. I paid for mine by working my butt off. No tax credit back then and only a very small deduction per dependent. This society of freeloaders is a disgrace. I guess having a fancy stable of cars and $400 a month cell phone bills are a lot more important to them.

I have a great idea, how about just all the democrats stop having children. But then we would still have the millions of the third worlders who are IN OUR COUNTRY ILLEGALLY who can’t stop having anchor babies. It doesn’t take a PhD to see what will happen over the coming decades to the gene pool.